Ebook Download All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow

Yeah, hanging out to review the book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow by on the internet can also provide you positive session. It will certainly reduce to talk in whatever condition. In this manner can be more interesting to do as well as less complicated to check out. Now, to obtain this All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow, you could download and install in the link that we provide. It will certainly assist you to obtain easy way to download and install the book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow.

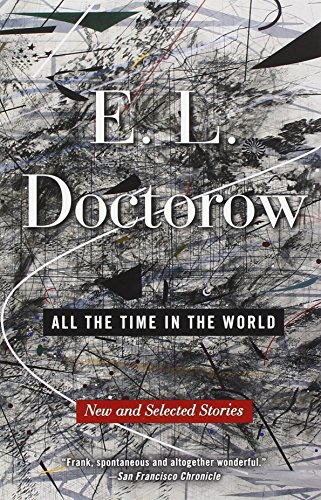

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow

Ebook Download All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow

All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow When writing can alter your life, when composing can improve you by supplying much money, why do not you try it? Are you still quite baffled of where understanding? Do you still have no concept with exactly what you are going to create? Currently, you will certainly need reading All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow A good writer is an excellent viewers at the same time. You could define exactly how you create depending on what books to review. This All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow could aid you to solve the trouble. It can be among the appropriate resources to establish your creating skill.

As known, book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow is well known as the home window to open up the world, the life, as well as brand-new point. This is just what individuals currently require a lot. Even there are many people which don't like reading; it can be a choice as referral. When you truly need the means to create the next inspirations, book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow will truly guide you to the way. Moreover this All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow, you will have no regret to obtain it.

To get this book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow, you may not be so confused. This is online book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow that can be taken its soft file. It is different with the on-line book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow where you can buy a book and after that the vendor will send the published book for you. This is the location where you can get this All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow by online and also after having manage buying, you can download All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow on your own.

So, when you need quick that book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow, it does not have to get ready for some days to obtain guide All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow You can directly obtain guide to conserve in your device. Also you love reading this All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow almost everywhere you have time, you could enjoy it to review All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow It is surely valuable for you that wish to obtain the much more valuable time for reading. Why don't you spend 5 mins as well as spend little money to get the book All The Time In The World: New And Selected Stories, By E.L. Doctorow here? Never ever allow the brand-new thing goes away from you.

From a master of modern American letters comes an enthralling collection of brilliant short fiction about people who, as E. L. Doctorow notes in his Preface, are somehow “distinct from their surroundings—people in some sort of contest with the prevailing world.” Containing six unforgettable stories that have never appeared in book form, and a selection of previous classics, All the Time in the World is resonant with the mystery, tension, and moral investigation that distinguish the fiction of E. L. Doctorow.

A reader’s guide can be found online at

RandomHouseReadersCircle.com

- Sales Rank: #722660 in Books

- Published on: 2012-01-24

- Released on: 2012-01-24

- Original language: English

- Number of items: 1

- Dimensions: 8.00" h x .60" w x 5.20" l, .50 pounds

- Binding: Paperback

- 304 pages

Review

“Frank, spontaneous and altogether wonderful.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“The . . . stories in All the Time in the World are a reminder that, for decades, Mr. Doctorow has been a first-rate artist in the short form.”—The Wall Street Journal

“The incandescent new stories and forever stunning vintage tales . . . selected for this powerhouse collection [are] complex and masterful . . . wise and resplendent.”—Booklist

“Wonderful descriptions [and] gorgeous sentences . . . seem to fall effortlessly from Doctorow’s fingertips.”—Chicago Tribune

“Savor All the Time in the World for its elegance, its intuition and for Doctorow’s understanding of the complexity of the human drama.”—The Miami Herald

“Doctorow has captured the mood of our time and rendered it in compelling fiction.”—The Philadelphia Inquirer

About the Author

E. L. Doctorow’s works of fiction include Welcome to Hard Times, The Book of Daniel, Ragtime, Loon Lake, World’s Fair, Billy Bathgate, The Waterworks, City of God, The March, Homer & Langley, and Andrew’s Brain. Among his honors are the National Book Award, three National Book Critics Circle awards, two PEN/Faulkner awards, and the presidentially conferred National Humanities Medal. In 2009 he was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, honoring a writer’s lifetime achievement in fiction, and in 2012 he won the PEN/ Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction, given to an author whose “scale of achievement over a sustained career places him in the highest rank of American literature.” In 2013 the American Academy of Arts and Letters awarded him the Gold Medal for Fiction. In 2014 he was honored with the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction.

From the Hardcover edition.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1

Wakefield

People will say that i left my wife and i suppose, as a factual matter, I did, but where was the intentionality? I had no thought of deserting her. It was a series of odd circumstances that put me in the garage attic with all the junk furniture and the raccoon droppings-which is how I began to leave her, all unknowing, of course- whereas I could have walked in the door as I had done every evening after work in the fourteen years and two children of our marriage. Diana would think of her last sight of me, that same morning, when she pulled up to the station and slammed on the brakes, and I got out of the car and, before closing the door, leaned in with a cryptic smile to say good-bye-she would think that I had left her from that moment. In fact, I was ready to let bygones be bygones and, in another fact, I came home the very same evening with every expectation of entering the house that I, we, had bought for the raising of our children. And, to be absolutely honest, I remember I was feeling that kind of blood stir you get in anticipation of sex, because marital arguments had that effect on me.

Of course, the deep change of heart can come over anyone, and I don't see why, like everything else, it wouldn't be in character. After having lived dutifully by the rules, couldn't a man shaken out of his routine and distracted by a noise in his backyard veer away from one door and into another as the first step in the transformation of his life? And look what I was transformed into-hardly something to satisfy a judgment of normal male perfidy.

I will say here that at this moment I love Diana more truthfully than ever in our lives together, including the day of our wedding, when she was so incredibly beautiful in white lace with the sun coming down through the stained glass and setting a rainbow choker on her throat.

On the particular evening I speak of-this thing with the 5:38, when the last car, where I happened to be sitting, did not move off with the rest of the train? Even given the sorry state of the railroads in this country, tell me when that has happened. Every seat taken, and we sat there in the sudden dark and turned to one another for an explanation, as the rest of the train disappeared into the tunnel. It was the bare, fluorescent-lit concrete platform outside that added to the suggestion of imprisonment. Someone laughed, but in a moment several passengers were up and banging on the doors and windows until a man in a uniform came down the ramp and peered in at us with his hands cupped at his temples.

And then when I do get home, an hour and a half later, I am nearly blinded by the headlights of all the SUVs and taxis waiting at the station: under an unnaturally black sky is this lateral plane of illumination, because, as it turns out, we have a power outage in town.

Well, it was an entirely unrelated mishap. I knew that, but when you're tired after a long day and trying to get home there's a kind of Doppler effect in the mind, and you think that these disconnects are the trajectory of a collapsing civilization.

I set out on my walk home. Once the procession of commuter pickups with their flaring headlights had passed, everything was silent and dark-the groomed shops on the main street, the courthouse, the gas stations trimmed with hedges, the Gothic prep school behind the lake. Then I was out of the town center and walking the winding residential streets. My neighborhood was an old section of town, the houses large, mostly Victorian, with dormers and wraparound porches and separate garages that had once been stables. Each house was set off on a knoll or well back from the street, with stands of lean trees dividing the properties-just the sort of old establishment solidity that suited me. But now the entire neighborhood seemed to brim with an exaggerated presence. I was conscious of the arbitrariness of place. Why here rather than somewhere else? A very unsettling, disoriented feeling.

A flickering candle or the bobbing beam of a flashlight in each window made me think of homes as supplying families with the means of living furtive lives. There was no moon, and under the low cloud cover a brisk unseasonable wind ruffled the old Norwegian maples that lined the street and dropped a fine rain of spring buds on my shoulders and in my hair. I felt this shower as a kind of derision.

All right, with thoughts like these any man would hurry to his home and hearth. I quickened my pace and would surely have turned up the path and mounted the steps to my porch had I not looked through the driveway gate and seen what I thought was a moving shadow near the garage. So I turned in that direction, my footsteps loud enough on the gravel to scare away whatever it was I had seen, for I supposed it was some animal.

We lived with animal life. I don't mean just dogs and cats. Deer and rabbits regularly dined on the garden flowers, we had Canada geese, here and there a skunk, the occasional red fox-this time it turned out to be a raccoon. A large one. I have never liked this animal, with its prehensile paws. More than the ape, it has always seemed to me a relative. I lifted my litigation bag as if to throw it and the creature ran behind the garage.

I went after it; I didn't want it on my property. At the foot of the outdoor stairs leading to the garage attic, it reared, hissing and showing its teeth and waving its forelegs at me. Raccoons are susceptible to rabies and this one looked mad, its eyes glowing, and saliva, like liquid glue, hanging from both sides of its jaw. I picked up a rock and that was enough-the creature ran off into the stand of bamboo that bordered the backyard of our neighbor, Dr. Sondervan, who was a psychiatrist, and a known authority on Down syndrome and other genetic misfortunes.

And then, of course, upstairs in the attic space over the garage, where we stored every imaginable thing, three raccoon cubs were in residence, and so that was what all the fuss was about. I didn't know how this raccoon family had gotten in there. I saw their eyes first, their several eyes. They whimpered and jumped about on the piled furniture, little ball-like humps in the darkness, until I finally managed to shoo them out the door and down the steps to where their mother would presumably reclaim them.

I turned on my cell phone to get at least some small light.

The attic was jammed with rolled-up rugs and bric-a-brac and boxes of college papers, my wife's inherited hope chest, old stereo equipment, a broken-down bureau, discarded board games, her late father's golf clubs, folded-up cribs, and so on. We were a family rich in history, though still young. I felt ridiculously righteous, as if I had fought a battle and reclaimed my kingdom from invaders. But then melancholy took over; there was enough of the past stuffed in here to sadden me, as relics of the past, including photographs, always sadden me.

Everything was thick with dust. A bull's-eye window at the front did not open and the windows on either side were stuck tight, as if fastened by the cobwebs that clung to their frames. The place badly needed airing. I exerted myself and moved things around and was able then to open the door fully. I stood at the top of the stairs to breathe the fresh air, which is when I noticed candlelight coming through the stand of bamboo between our property and the property behind ours, that same Dr. Sondervan's house. He boarded a number of young patients there. It was part of his experimental approach, not without controversy in his profession, to train them for domestic chores and simple tasks that required their interaction with normal people. I had stood up for Sondervan when some of the neighbors fought his petition to run his little sanatorium, though I have to say that in private it made Diana nervous, as the mother of two young girls, that mentally deficient persons were living next door. Of course, there had never been a bit of trouble.

I was tired from a long day, that was part of it, but, more likely suffering from some scattered mental state of my own, I groped around till I found the rocking chair with the torn seat that I had always meant to recane, and, in that total darkness and with the light of the candles slow to fade in my mind, I sat down and, though meaning only to rest a moment, fell asleep. And when I woke it was from the light coming through the dusty windows. I'd slept the night through.

what had brought on our latest argument was what I claimed was Diana's flirtation with someone's houseguest at a backyard cocktail party the previous weekend.

I was not flirting, she said.

You were hitting on the guy.

Only in your peculiar imagination, Wakefield.

That's what she did when we argued-she used the last name. I wasn't Howard, I was Wakefield. It was one of her feminist adaptations of the locker-room style that I detested.

You made a suggestive remark, I said, and you clicked glasses with him.

It was not a suggestive remark, Diana said. It was a retort to something he'd said that was really stupid, if you want to know. Everyone laughed but you. I apologize for feeling good on occasion, Wakefield. I'll try not to feel that way ever again.

This is not the first time you've made a suggestive remark with your husband standing right there. And then denied all knowledge of it.

Leave me alone, please. God knows you've muzzled me to the point where I've lost all confidence in myself. I don't relate to people anymore. I'm too busy wondering if I'm saying the right thing.

You were relating to him, all right.

Do you think with the kind of relationship I've had with you I'd be inclined to start another with someone else? I just want to get through each day-that is all I think about, getting through each day.

That was probably true. On the train to the city, I had to admit to myself that I'd started the argument willfully, in a contrary spirit and with some sense of its eroticism. I did not really believe what I had accused her of. I was the one who came on to people. I had attributed to her my own wandering eye. That is the basis of jealousy, is it not? A feeling that your congenital insincerity is a universal? It did annoy me, seeing her talking to another man with a glass of white wine in her hand, and her innocent friendliness, which any man could mistake for a come-on, not just me. The fellow himself was not terribly prepossessing. But it bothered me that she was talking to him almost as if I were not standing there beside her.

Diana was naturally graceful and looked younger than she was. She still moved like the dancer she had been in college, her feet pointed slightly outward, her head high, her walk more a glide than something taken step by step. Even after carrying twins, she was as petite and slender as she had been when I met her.

And now in the first light of the new day I was totally bewildered by the situation I had created for myself. I can't claim that I was thinking rationally. But I actually felt that it would be a mistake to walk into my house and explain the sequence of events that had led me to spend the night in the garage attic. Diana would have been up till all hours, pacing the floor and worrying what had happened to me. My appearance, and her sense of relief, would enrage her. Either she would think that I had been with another woman or, if she did believe my story, it would strike her as so weird as to be a kind of benchmark in our married life. After all, we had had that argument the previous day. She would perceive what I told myself could not possibly be true-that something had happened predictive of a failed marriage. And the twins, budding adolescents, who generally thought of me as someone they were unfortunate to live in the same house with, an embarrassment in front of their friends, an oddity who knew nothing about their music-their alienation would be hissingly expressive. I thought of mother and daughters as the opposing team. The home team. I concluded that for now I would rather not go through the scene I had just imagined. Maybe later, I thought, just not now. I had yet to realize my talent for dereliction.

when i came down the garage stairs and relieved myself in the stand of bamboo, the cool air of the dawn welcomed me with a soft breeze. The raccoons were nowhere to be seen. My back was stiff and I felt the first pangs of hunger, but, in fact, I had to admit that I was not at that moment unhappy. What is there about a family that is so sacrosanct, I thought, that one should have to live in it for one's whole life, however unrealized one's life was?

From the shadow of the garage, I beheld the backyard, with its Norwegian maples, the tilted white birches, the ancient apple tree whose branches touched the windows of the family room, and for the first time, it seemed, I understood the green glory of this acreage as something indifferent to human life and quite apart from the Victorian manse set upon it. The sun was not yet up and the grass was draped with a wavy net of mist, punctured here and there with glistening drops of dew. White apple blossoms had begun to appear in the old tree, and I read the pale light in the sky as the shy illumination of a world to which I had yet to be introduced.

At this point, I suppose, I could have safely unlocked the back door and scuttled about in the kitchen, confident that everyone in the house was still asleep. Instead, I raised the lid of the garbage bin and found in one of the cans my complete dinner of the night before, slammed upside down atop a plastic bag and held in a circle of perfect integrity, as if still on the plate-a grilled veal chop, half a baked potato, peel-side up, and a small mound of oiled green salad- so that I could imagine the expression on Diana's face as she had come out here, still angry from our morning argument, and rid herself of the meal gone cold that she had stupidly cooked for that husband of hers.

From the Hardcover edition.

Most helpful customer reviews

16 of 16 people found the following review helpful.

An Author For All Time

By Jill I. Shtulman

E.L. Doctorow is without a doubt one of the most critically acclaimed authors publishing in America today. He has enthralled me with Ragtime, mesmerized me with Homer & Langley, snapped me to attention with March, and provoked me to think outside of the box with The Book of Daniel.

But even though I've periodically read his short stories in The New Yorker, I never quite viewed him as a "short story writer." Well, after finishing All The Time in the World, that perception has definitely changed.

Stylistically, Doctorow has been described as a nomad, leaping across styles and genres and this collection is no exception. The reader must dig hard to discover a thread that connects these disparate stories, finally deferring to Doctorow's own judgment as defined in the preface, "I see there is no Winesburg here to be mined for humanity... What may unify them is the thematic segregation of their protagonists. The scale of a story causes it to home in on people who, for one reason or another, are distinct from their surroundings - people in some sort of contest with the prevailing world."

Take these stories for example: an affluent lawyer at the end of an ordinary workday decides to become an observer of his own life, hiding within feet of his wife and twin daughters. As he pares his life down to the bare essentials, it is only the thrill of competition that brings him back once again.

A husband and wife - who have elevated verbal sparring to a fine art - see their relationship exposed in bare relief when a homeless poet who once lived in their home enters their life.

A young immigrant, with aspirations to produce films, takes a dishwasher's job in a criminal enterprise, and agrees to marry the top honcho's beautiful niece for money. Yet this mercenary decision entangles him in a greater emotional involvement than he ever expected.

A teenage boy named Jack - the writer in the family - is prevailed upon by an aunt to write letters to his ancient grandmother in the voice of his recently deceased father...until he comes face to face with his father's real dream of life.

And, in the eponymous final story, an urban citizen, out for a typical morning run, no longer recognizes his city and suspects that a nefarious Program has put him there without his consent.

These wide-ranging pieces span time, American geography, and social strata: they're set in New York City, a nameless but instantly recognized suburbia, the deep south, the Midwest. They move from the late nineteenth century to a moment in the future. They are populated with disenchanted lawyer, a down-on-her-luck teenager, an increasingly cynical priest, even a son of a serial murderer. They sing with tension, poignancy, and authenticity. And they evoke the past, present and future in ways that are both mysterious and familiar.

In short, this is yet the latest indication that E.L. Doctorow is an author not only for our times, but for all time. The book contains six memorable stories that have never appeared in book form combined with a selection of beloved Doctorow classics.

4 of 4 people found the following review helpful.

A Varied Collection

By Sam Sattler

E.L. Doctorow's new short story collection, All the Time in the World, is a collection of twelve stories that have been published previously in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Kenyon Review, and The New American Review. Moreover, six of the stories have been included in previous short story collections, meaning that only six of the twelve are appearing in book form for the first time. Because, as the book jacket notes, the stories were written over a period of "many years," the collection is an opportunity for first-time readers of Doctorow short stories to experience a representative selection of styles favored by the author.

And, stylistically, these stories are all over the map. That means, of course, that the appeal of individual stories will vary from reader to reader. I, for example, generally favor stories with relatively direct approaches to plot and theme, and I consider it a bonus if the stories also offer fully developed characters. Stories with a less linear approach, particularly those that use a stream-of-consciousness style, work less successfully for me. Several of the stories in All the Time in the World are of that type - and two or three of them, I confess, did leave me a bit mystified.

Several of these dozen stories are particularly notable, including the first in the collection, "Wakefield." This is the story of a businessman who, almost by accident, fails to return to his family one evening after the return leg of his work commute is disrupted by a massive power failure. Instead, he hides out above the family garage, from where - over several months - he watches his wife and two daughters get on with the rest of their lives while he creates a strange new existence for himself.

Among other topics, are stories about a murderous mother and son, an inane religious cult, women hardened by life's demands, a stranger who longs only to get inside his childhood home one more time, and a teenage boy obliged to write letters from his dead father to his senile grandmother. One story happens in the small town America that existed shortly after the Civil War, others in America's large modern cities and suburbs.

Taken as a whole, the stories confirm that E.L. Doctorow is, despite his having produced so few short stories over his long career, a master of that craft. Although the author will always be thought of first as a novelist, the stories selected for All the Time in the World prove he can write short stories with the best of his peers.

5 of 6 people found the following review helpful.

E.L. Doctorow continues to shine

By Bookreporter

If E. L. Doctorow and his publisher had wanted to choose an apt title for his third collection of short stories, they might have called it "American Misfits." Although in a brief preface he expresses doubt that "stories collected in a volume have to have a common mark, or tracer, to relate them to one another," in virtually all of these tales, spanning more than 150 years of this country's history, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author portrays troubled individuals struggling to make sense of their lives in a society that exalts individualism over community.

No story better illustrates that unity than "Wakefield," which opens the volume. Drawing its inspiration from the same wellspring as John Cheever's classics "The Country Husband" or "The Swimmer," Doctorow describes a character who stumbles back to his suburban home after a power outage strands his commuter train and decides to take up residence in his detached garage, vanishing from his life in the process. Doctorow renders that bizarre premise completely plausible, as Howard Wakefield, a seemingly successful New York City attorney, manages to slip the bonds of his crumbling marriage. "I lived in Diana's judgment," he observes of his wife on the night of his fateful decision, "it shone upon me as in a prison cell where the light is never turned off."

"Walter John Harmon" and "Heist" both deal with characters experiencing crises of faith. The narrator of the former story lives in a community led by a Jim Jones/David Koresh-like character who makes off with both the narrator's wife and the community's treasury. The story's concluding sentence is as chilling as any to be found in recent short fiction. Thomas Pemberton, the protagonist of "Heist," is a troubled Episcopal priest facing professional discipline for his sermons fueled by a growing skepticism. "Why must faith rely on innocence," he asks. "Must it be blind? Why must it come of people's need to believe?"

Doctorow doesn't limit himself to male protagonists. In "A House on the Plains" (a tale that seems to share its lineage with the best of Stephen King's mature short fiction), he tells the story of a murderous widow in post-Civil War Illinois. "Jolene: A Life" recounts 10 nomadic years in the life of a young woman who marries at 15 and then flees a series of disastrous relationships across the United States, from South Carolina to West Hollywood.

What is consistent in all of these stories is the measured elegance of Doctorow's prose and the incisiveness of his character portraits. "Edgemont Drive" is the story of a man who appears one day at a home where he claims he once lived. His arrival exposes the fault lines in the occupants' marriage:

"When people speak of a haunted house, they mean ghosts flitting about in it, but that's not it at all. When a house is haunted --- what I'm trying to explain --- it is the feeling you get that it looks like you, that your soul has become architecture, and the house in all its materials has taken you over with a power akin to haunting. As if you, in fact, are the ghost."

Not all of the stories hit the mark. There are times, as in "Liner Notes: The Songs of Billy Bathgate," (no apparent relation to the title character of Doctorow's novel about Depression-era mobsters), a series of sketches of the lives of two folk musicians, that his treatment of the subject matter feels almost willfully obscure. "The Hunter," the brief story of a young school teacher and menacing bus driver, suffers from the same infirmity.

Given Doctorow's age (he turned 80 in January) and stature in the literary world, it's also fair to ask why Random House hasn't seen fit yet to produce a volume of collected stories. The current collection contains six stories that appeared either in SWEET LAND STORIES, published in 2004, or in 1984's LIVES OF THE POETS. Four of the remaining six stories, including one later adapted for his novel CITY OF GOD, were first published in The New Yorker. It would hardly be a stretch to assemble his relatively small output of short fiction in one place.

These quibbles aside, the publication of any new work by this American master is something to celebrate. Coming on the heels of strong late-career novels like THE MARCH and HOMER & LANGLEY, we can hope Doctorow's fiction will continue to provoke and move us.

--- Reviewed by Harvey Freedenberg

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow PDF

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow EPub

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow Doc

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow iBooks

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow rtf

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow Mobipocket

All the Time in the World: New and Selected Stories, by E.L. Doctorow Kindle

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar